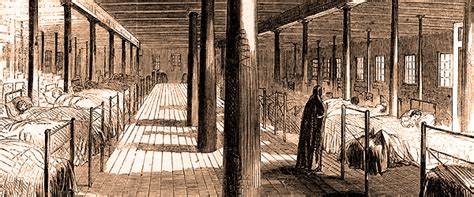

It was just another day at Vienna General Hospital when a young man in his late twenties, eager and fresh-faced, enthusiastically entered through the doors. Newly employed, Doctor Ignaz Semmelweis, was determined to make a good first impression. Although new, he was entrusted with important work including overseeing patient care and updating hospital administrators on ward successes and failures. The hospital had two obstetric units that he oversaw; the first clinic was run by male physicians and students, and the second clinic was overseen by midwives and trainees (Semmelweis Pg. 63).

It wasn’t long before the new assistant of the maternity clinics was faced with a grim problem. The death rate from puerperal fever (termed childbed fever), a bacterial infection leading to sepsis, was alarmingly higher in the first clinic. Semmelweis later recounted how pregnant women begged on their hands and knees not to be admitted to the first clinic, oftentimes coming to hysterics. In some extreme cases, they fled the hospital altogether and chose instead to give birth on the street (Semmelweis Pg. 67).

This troubling death rate consumed his mind. He became obsessed with why women were dying of childbed fever and why the number of deaths were higher in one clinic. Semmelweis’ investigation was met with skepticism by colleagues, some of which believed the disease to simply be unpreventable. With the lives of vulnerable women at stake, Semmelweis would not, could not, accept that nothing could be done. The work he would later go on to do at Vienna General Hospital would not only change the trajectory of his life, but would forever alter the field of obstetrics and gynecology.

Ignaz Semmelweis was born on July 1, 1818 in Hungary to Theresia Müller and Joseph Semmelweis. Both parents were of German descent, and after obtaining citizenship in Buda, Hungary opened a successful merchant business selling consumer goods (Ataman). He was the fifth of ten children and grew up in a prosperous household. Ignaz and his siblings were raised with a strong religious background and attended Catholic high school (Ataman). With abundant resources and familial support, he went on to study law at the University of Vienna in 1837 (Ataman). After some time, he decided that a career in law was not for him and switched to medicine, graduating in 1844 (Ataman). It is believed that he originally sought out a position in internal medicine, but after being passed over was inspired by his mentors at the time to consider working in obstetrics. The men he had grown close working relationships with while at university helped him acquire an analytical form of thinking that he would later utilize while searching for rational solutions to combat childbed fever.

It didn’t take the young doctor long to settle into a routine. Each morning, Semmelweis made his rounds, visiting the women admitted to the clinics to assess their conditions and provide the head professor with updates (Sinclair, Pg. 15). During these visits, he witnessed the devastating effects of childbed fever. Watching new mothers suffer and die prematurely deeply affected him. Dissatisfied with merely fulfilling his general duties, Semmelweis was determined to make a real difference. He dedicated himself to investigating the cause of the illness with a methodical, research-driven approach; going beyond the traditional scope of his responsibilities in a desperate pursuit of answers.

Subsequently, an exhaustive couple of months began for Doctor Semmelweis as he explored every possible explanation as to why lying-in women were getting sick. At this point in history, many medical professionals believed in the miasma theory, that illnesses were caused by atmospheric factors including bad smells and toxic air. Due to this general belief, Semmelweis wanted to ascertain whether the air conditions and temperatures in the clinics differed. Both clinics had seemingly identical atmospheric conditions but he did recommend windows be regularly opened to allow fresh air in and improve ventilation within the rooms. He looked at the foods that patients were given and found no cause for concern because the dishes were identical. It was suggested that he check into the laundering process and see whether or not bedding was being mixed with laundry from the general hospital. It was quickly learned that the bedding from the first and second clinic were laundered by the same contractor and mixed in the same way with linens from the general hospital wards (Semmelweis (Pg. 75).

The idea was proposed to him that the bad reputation of the first clinic and hospitals in general was making the women sick. It was thought that women were becoming so fearful of death that they were dying themselves. Exploring the idea of fear, he evaluated the effect that priests performing last rites had on other women in the ward. A priest adorned in ceremonial robes slowly trailing the halls while rhythmically ringing an eerie bell as a final death rite was a depressing sight. Everyone’s spirits were lowered after such a visit. The bell that the priests rang through the hallways was upsetting patients, so Semmelweis rerouted the holy men so that their presence was less obvious. In his later published work he described the bells as such, “Even to me myself it had a strange effect upon my nerves when I heard the bell hurried past my door; a sigh would escape my heart for the victim that once more was claimed by an unknown power.”(Sinclair Pg. 36-37) He did not understand how a psychological condition, fear, could bring about childbed fever though, and came to dismiss such theories as a leading cause. (Semmelweis Pg. 71). Going further with uncanny theories was that women were actually taking ill as a result of wounded modesty from male doctors examining them (Sinclair Pg. 38). He did not find it plausible that modesty was an etiological factor in puerperal fever, even noting that many women in active labor simply did not seem overly preoccupied with modesty. It was also discussed whether or not the women, many who were impoverished, were developing the sickness due to harsh environmental factors before entering the clinic. This train of thought held no merit though because both clinics housed poor women, so why were more contracting and dying of childbed fever in the first clinic if they were both exposed to it outside of the hospital? Admission into the first and second clinic changed over every 24-hours except on weekends, when the first clinic took admissions for a 48-hour period. Therefore, both clinics were housing women from the same walks of life. There was no reason at all, as far as Semmelweis saw it, to believe that the women were sick before coming to the hospital. If they were, both clinics would have similar reported death rates.

After a death occurred, Semmelweis took observations of the body and read through all notes about their stay. This process revealed to him that women whose labors were longer, meaning they were dilated for a period longer than 24 hours, seemed to become ill the most frequently (Semmelweis Pg. 75). Although a keen observation, he did not know what to do with the information nor exactly what that meant. After tireless research and no probable cause or hypothesis, Semmelweis became increasingly exhausted. He was beginning to worry that he was missing something obvious. Frustrated and in need of a break, Semmelweis took a short leave to rest in Venice, hoping that he could return with a clear mind.

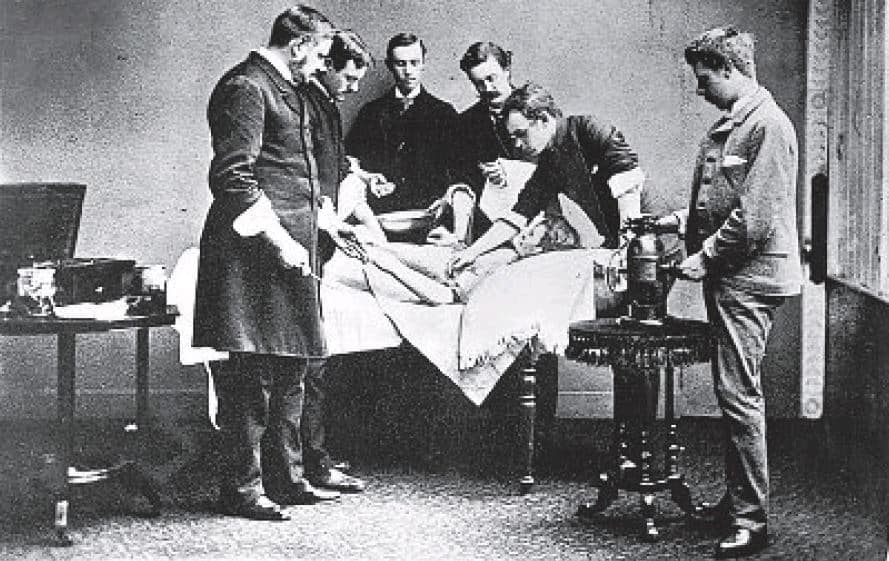

Upon his return, he heard that a colleague had died, professor Kolletschka. He had nicked his finger during an autopsy of a woman with childbed fever and his subsequent symptoms were the same. Semmelweis concluded that he died from cadaveric materials entering into the vascular system via the knife puncture. He put it together that the same cadaveric materials were being introduced into the women’s systems (Sinclair 49). This tragic yet serendipitous moment was a major breakthrough because it meant that childbed fever did not only impact laboring women, it could be spread from person to person. The knife cut was the obvious entry point and began suspecting that the cadaveric particles that would have been on his hands to be the cause of the illness. With that information, he concluded that the complex question he had been obsessing over the past few months had a very simple answer. The reason for the higher death rates in the first clinic was a direct result of the male physicians. Only the male doctors and their students were performing autopsies, not midwives. This meant that they were performing autopsies, then taking their unwashed hands which contained cadaveric particles, and infecting the women they later assisted in childbirth.

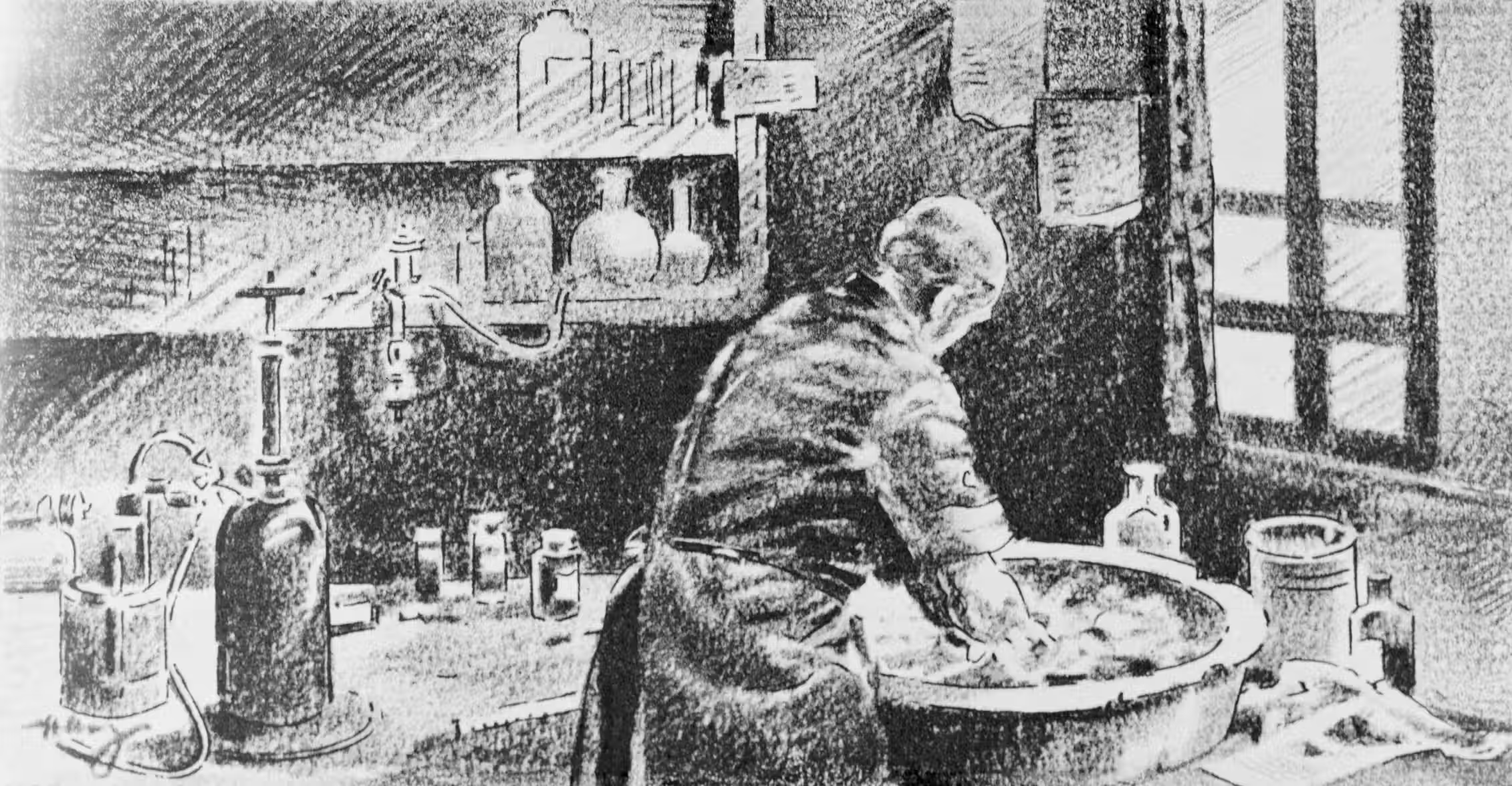

Now that he had his answer, he needed to come up with a preventive solution. He insisted that all personnel wash their hands thoroughly in a chlorine solution (Davis). In his mind, the chlorine solution was strong enough to work on the particles because it took the smell away from the skin. Over the course of seven months, the death rate dropped from around 12% to 3% (Sinclair 49). By that point, the rate of childbed fever deaths was almost identical between the two clinics. Although effective, in a time before germ theory, Semmelweis had no real way to scientifically prove his ideas. Many medical professionals refused to accept that their actions were directly resulting in patient death. Throughout the course of the rest of his professional career, he would go on to help save the lives of countless women. He would also be cursed with constant, harsh criticism and rejection. He was known to have responded to criticism by calling doctors negligent murderers.

His eccentric nature made him a public pariah. In 1861 he published his works and tried to train medical professionals about the importance of handwashing in public health. Doctor Semmelweis would marry Mária Weidenhofer and have three children. Unfortunately, his mental health began deteriorating and he became known for angry outbursts and drunkenness. By 1865 his depression and cognitive disorders became so bad that he was admitted to a mental institution where he would die two weeks later. He was not vindicated nor his ideas widely accepted until the work of Louis Pasteur and Doctor Joseph Lister gave rise to antiseptic surgical procedures and preventive care. In his day, he was a laughingstock, but today we know him as the savior of mothers.

“When, with my current convictions, I look into the past, I can endure the miseries to which I have been subjected only by looking at the same time into the future; I see a time when only cases of self-infection will occur in the maternity hospitals of the world. In comparison with the great numbers thus to be saved in the future, the number of patients saved by my students and by me is insignificant. If I am not allowed to see this fortunate time with my own eyes, therefore, my death will nevertheless be brightened by the conviction that sooner or later this time will inevitably arrive.” (Semmelweis Pg. 250)

If you enjoyed this longer post, please give it a like!

Until Next Time

N.F.

Sources:

- Ataman, A. D.; Vatanoğlu-Lutz, E. E.; Yıldırım, G. “Medicine in stamps-Ignaz Semmelweis and Puerperal Fever.” Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association. March 2013.DOI 10.5152/jtgga.2013.08. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3881728/. Accessed 28 January, 2025.

- Davis, Rebecca. “The Doctor Who Championed Hand-Washing And Briefly Saved Lives.” NPR. January 12, 2015. Accessed 21 January, 2025. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/01/12/375663920/the-doctor-who-championed-hand-washing-and-saved-women-s-lives

- Kadar, Nicholas, Roberto Romero, Zoltán Papp. “Ignaz Semmelweis: the “Savior of Mothers”:On the 200th anniversary of his birth.” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Volume 219, Issue 6, Page 519-522. December 2018. Accessed 30 January, 2025. https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(18)30943-8/fulltext.

- Loudon, Irving. “Semmelweis and his thesis.”JRSM: Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.” December, 2005. Accessed 21 January, 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1299347/

- Parker, Steve. Medicine: The Definitive Illustrated History. DK Publishing: New York, 2016. Accessed 23 January, 2025. Print.

- Paul, Sheuli, Shradha Salunkhe, Kasireddy Dravanthi, and Shailaja Mane. “Pioneering Hand Hygiene: Ignaz Semmelweis and the Fight Against Puerperal Fever.” Cureus. October 17, 2024. Accessed 30 January, 2025. https://www.cureus.com/articles/283961-pioneering-hand-hygiene-ignaz-semmelweis-and-the-fight-against-puerperal-fever#!/.

- Semmelweis, Ignaz. The etiology, concept, and prophylaxis of childbed fever. Translated by K. Codell Carter. Madison, Wis. : University of Wisconsin Press, 1983. Internet Archive. Accessed 21 January, 2025.

- Sinclair, William.“Semmelweis: his life and doctrine : A chapter in the history of medicine.” Internet Archive. Manchester : University Press, 1908. Accessed 3 February, 2025. https://archive.org/details/b2151270x/mode/2up.