Most women of reproductive age will experience numerous gynecological appointments during their lifetimes. Gynecology is the branch of medicine centered around women’s reproductive systems that looks to prevent, diagnose, and treat related disorders and complications. A visit to such an office is oftentimes physically uncomfortable and intimate in nature. It is difficult to fathom how profoundly traumatic that experience would become if someone were forced to endure such invasive procedures without consent or choice. Unfortunately, that was the case for many black women during the 1800s. The modern field of gynecology has deep roots in racism and the man behind it all practiced his techniques on nonconsenting black women who were slaves in the South.

Nicknamed the “Father of Modern Gynecology,” Dr. James Marion Sims began his medical career after graduating from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1835. At first, he did not feel particularly passionate about his career choice. For the next year to two-year stint, he stayed on in Pennsylvania and struggled to find his footing. Many of his early patients died or were misdiagnosed. In 1837, he decided to relocate to Alabama where he would make a name for himself as a plantation physician. During that time, he performed a wide variety of surgical treatments on enslaved men and women. It wasn’t until he again relocated to Montgomery, Alabama that he came to heavily focus on gynecology-a field of medicine that did not yet exist at the time. By 1840, he had established a small four bed hospital in his backyard, which he later expanded to hold eight beds in total.

“I felt no particular interest in my profession at the beginning of it apart from making a living…. I was really ready at any time and at any moment to take up anything that offered, or that held out any inducement of fortune, because I knew that I could never make a fortune out of the practice of medicine.”

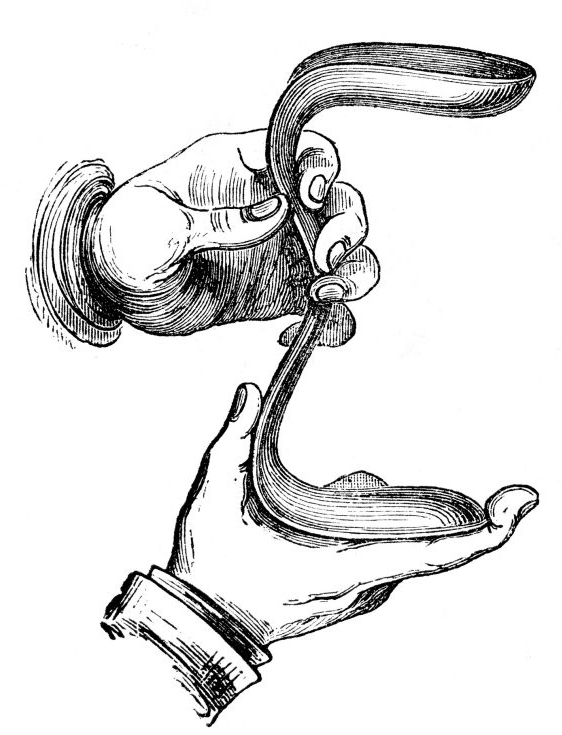

Part of the reason why he worked with women so frequently was the fact that women suffering from reproductive health complications were unable to work as much and were limited in childbearing. The owners of the plantations valued production and reproduction from their enslaved women because it made them more money and secured workers for the next generation. During this time, many male physicians found examining women’s reproductive organs absolutely repulsive. Dr. Sims also voiced a distaste for the task. By 1845, he had witnessed a female patient who was experiencing severe complications due to a vesicovaginal fistula. Such fistulas, although typically not fatal, were a common complication that was rather loathsome to endure. The condition consists of a tear between the uterus and bladder that usually occurs during childbirth and leads to incontinence. It can cause infections, an inability to bear more children, extreme pain, embarrassing odors, and high fevers. Women with this condition were marginalized from society and outcasted by social groups. Dr. Sims first observed the condition by internally examining a female patient who had fallen off of a horse and sustained injuries. The need to see into the vagina to examine her pelvis and surrounding tissues led him to develop the first speculum-a tool that allows physicians to see into the vaginal canal. The first speculum consisted of little more than pewter spoons used to stretch the opening.

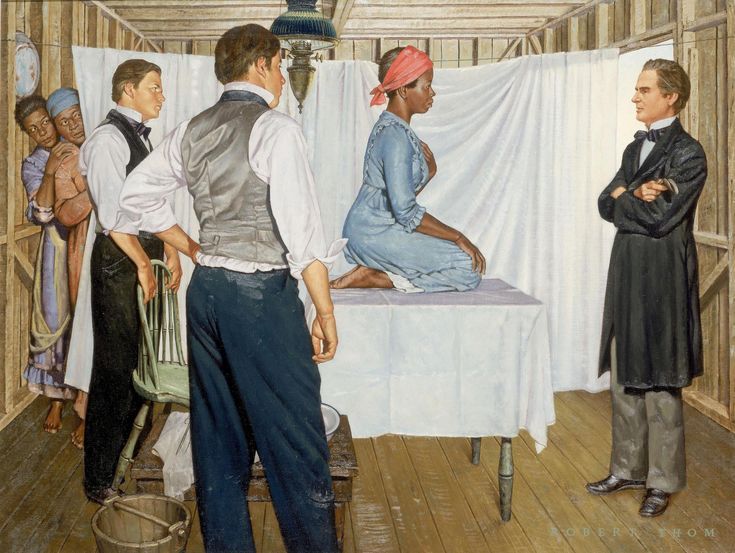

Although he is not the first person the treat vesicovaginal fistulas, he is credited with developing practices that continue to impact the gynecology field. The main subjects of his surgical experiments were black slaves who were brought to his hospital by their owners. They were unable to consent to the treatments that they received. It is plausible that many of those women who were experiencing complications would have been relieved to be treated, but their inability to choose to participate in his experiments has created a lot of ethical concerns. The women were stripped of their clothing and were examined in a room that often contained multiple male students. Advancements were made in anesthesia thanks to the Civil War, but Dr. Sims held the racist belief that black people did not feel pain to the same degree as white people. This meant that almost all of his surgical procedures were done without the use of anesthesia.

Some women had to undergo several surgeries to fix their problems, giving Dr. Sims plenty of opportunities to master his techniques. Although he was widely celebrated in the South, his reputation was precarious for several reasons. Some people found his practices to be extreme, cruel, and downright unethical. Most of his medical breakthroughs can be credited to twelve slave women who were “on loan” to him. Only 3 out 12 of their names have not been lost to time (Betsy, Lucy, and Anarcha). After perfecting his practice, he would go on to perform his surgical techniques on white women. Later in life, he moved to New York and opened a women’s hospital, one of the first of its kind. Countless women continue to benefit every year from the contributions Dr. Sims made to the field of modern Gynecology. I also want to extend my gratitude to the women who contributed as well. If he is considered the “Father of Modern Gynecology,” then they are the “Mothers of Modern Gynecology.” Their sacrifices should surely not be overlooked nor forgotten.

Thank you for reading!

Until Next Time

N.G.

References:

-Brynn Holland, “The ‘Father of Modern Gynecology’ Performed Shocking Experiments on Enslaved Women,” History, A&E Television Networks, last modified December 03, 2025, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www/history.com/articles/the-father-of-modern-gynecology-performed-shocking-experiments-on-slaves

-Mütter EDU Staff. “James Marion Sims: Father of Modern Gynecology or Abuser?” Mütter Museum Stories. September 24, 2020. Accessed February 19, 2026. https://muttermuseum.org/stories/posts/james-marion-sims-father-modern-gynecology-or-abuser/

-Vernon, Leonard F. “J. Marion Sims, MD: Why He and His Accomplishments Need to Continue to be Recognized — A Commentary and Historical Review.” Journal of the National Medical Association 111, no. 4 (August 2019): 436–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2019.02.002